Each virus and bacterium triggers a unique response in the immune system involving a specific set of cells in the blood, in the bone marrow, and all over the body, called T-cells, B-cells, among others.

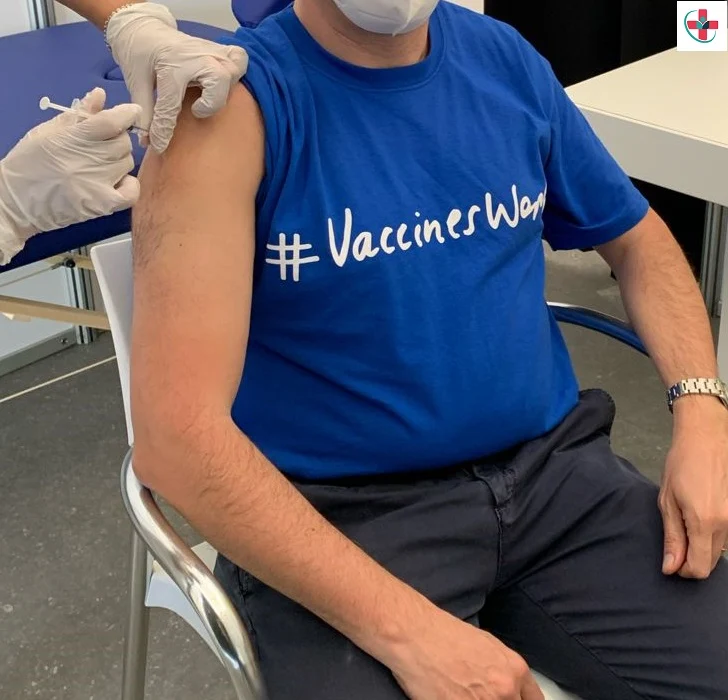

A vaccine stimulates an immune response, and a ‘memory’ of the body to a specific disease, without causing the disease.

Most vaccines contain a greatly weakened or an inactivated (killed) form of a virus or bacterium that usually causes a disease or a small part of the virus or bacterium. This is called the antigen.

When a person is given the vaccine, their immune system recognizes the antigen as ‘foreign’. This activates the immune system cells so that they kill the disease-causing virus or bacterium and make antibodies against it. Antibodies are special proteins that help kill the virus or bacterium.

Later, if the person comes into contact with the actual infectious virus or bacterium, their immune system will ‘remember’ it. It will then quickly produce the right antibodies and activate the right immune cells to kill the virus or bacterium, protecting the person from the disease.

Immunity usually lasts for years, and sometimes for a lifetime. The length of time varies by disease and by the vaccine.

Immunity through vaccination protects not only the immunized individual but also protects unvaccinated people in the community, such as infants who are too young to be vaccinated. This ‘community immunity’ can only work if enough people are vaccinated.

In contrast, a person who becomes immune by getting the disease can expose other unvaccinated people to the disease. The person is also at risk of complications.

Some newer vaccines do not contain an antigen. Instead, they contain ‘instructions’ that tell the body’s cells how to make an antigen that is identical to a small part of a real virus.

These instructions can be:

* mRNA in an mRNA vaccine; or

* a modified, harmless virus, in a viral-vector vaccine.

When a person is given an mRNA or a viral-vector vaccine, some of their cells read the instructions. These cells then produce the antigen for a short time before they break down the mRNA or the harmless virus.

The person’s immune system then recognizes the antigen as ‘foreign’, activating immune cells and making antibodies. Some COVID-19 vaccines work using mRNA or a modified virus.

Herd immunity

When someone is vaccinated, they are very likely to be protected against the targeted disease. But not everyone can be vaccinated. People with underlying health conditions that weaken their immune systems (such as cancer or HIV) or who have severe allergies to some vaccine components may not be able to get vaccinated with certain vaccines. These people can still be protected if they live in and amongst others who are vaccinated. When a lot of people in a community are vaccinated the pathogen has a hard time circulating because most of the people it encounters are immune. So the more that others are vaccinated, the less likely people who are unable to be protected by vaccines are at risk of even being exposed to harmful pathogens. This is called herd immunity.

This is especially important for those people who not only can’t be vaccinated but may be more susceptible to the diseases we vaccinate against. No single vaccine provides 100% protection, and herd immunity does not provide full protection to those who cannot safely be vaccinated. But with herd immunity, these people will have substantial protection, thanks to those around them being vaccinated.

Vaccinating not only protects yourself but also protects those in the community who are unable to be vaccinated. If you are able to, get vaccinated.